The Great Global Gobble, Part Two

A sad reflection it is, considering how the Master of Business Arts represents “the” college degree. No more philosophy, humanities chucked, foreign language out the door, screw you to history, whereas a diploma in business is now the hallmark of a college education, which in turn converts the university into a trade school. This piece may seem like a sign of personal neurosis, throwing dung at the temple of profit, but since a majority of acolytes worship business, an overview seems in order.

☞ Having been in business myself, I respect the profit motive— when it’s respectable. Calvin Coolidge’s affirmation that the “business of America is business” holds up as an attitude growing naturally out of a “nation of shopkeepers.” Most of the action is small business (at one point 70%) because it seems that a huge American industrial hiccup has settled down to shopkeeper level. Which in turn might be why an attitude adjustment toward business might be in order.

☞ The problem just might be how the modern business man, with his willingness to sell most anything for profit, sold most of his means of production, perhaps in some cases his soul, and the consumer took the fall.

President Obama was only the latest to follow the chump trail, hat in hand, making a remarkable show of obsequiousness to Asia and assuming the position. The Middle East, along with Asia, serve as a historical mirror to American economic destiny. Isn’t that essentially what the Boxer Rebellion was about?

It’s already been recorded here in Trying Times annals how Americans decided China was ready to do business and go to church. Americans believed with the faith of little children that China was full of folks ready to buy their stuff and give thanks to God for it. So they went over, messed around doing their commercial messianic thing, and got a fight going— the Boxer Rebellion— with the natives who really didn’t care to have a bunch of westerners around befouled with the stink of butter. So an allied coalition of soldiers, mostly American dough boys, had to go over there, over there (Sound familiar?) to straighten things out. That was in 1900. At the end of the same century, American business agents were groveling en masse in Asia to repeat the process.

☞ In Tokyo those of us schooled in academic fields lesser than commerce referred to the business people as mostly saps. Business saps. Why? Because not much seems to have been learned in over a century of dealing with Asia. It was clear they were just as desperate to make as desperate deals as their predecessors.

American corporate desperation is apparent wherever one looks, but the world has been living with one obvious example. It began when greedy lawyers extracted record amounts of moral gelt by reaming tobacco producers. Social demand for this reaming was justified over a product which, though as traditional as Humphrey Bogart, actually killed people. Tobacco companies were forced, in their lingo, to “restrategize.” Translation: relocate. Since Asia was full of smokers, it presented an obvious target. Or so they thought.

Tobacco manufacturers were only the latest in a long line. When domestic commercial tobacco was reefed, it was “head for the long boats and go East young man!” Tobacco kings thought that Asia was their deliverance. Yes, they sold logos. Marlboro’s logo is as ubiquitous in Asian cities as the local temple. But everything else came through Japanese or Chinese or Singapore manufactures. Who knows the details? Perhaps some American tobacco was sold to these overseas outlets. But the lion’s share was made in Asia by Asians for Asians. If anyone was going to hook the people of Japan or Korea, it would be Japanese or Koreans.

And the Asians led the westerners along. I personally knew of one attempt to break into the Asian smoking market by an American/Japanese company that made a bid to buy the Harley Davidson logo, replete with a logo of a Harley hog. Harley cigarettes would have been produced in Japan, and perhaps the few American tobacco growers who still existed might have benefited. But since the market is global, they weren’t much likely to be enriched even if the company had succeeded. It did not. The entrepreneurs went broke just buying the logo.

☞ Americans should be proud to have at hand what they themselves promoted: world-wide free market capitalism. But there remains hardly anything to be proud of. The few American producers left are not really basking in the competition. Such was definitely the case when I observed some biz guyz doing a hat-in-hand kabuki while trying to get something out of Honda Motors.

In the late 80s, during the height of Japanese business ascendancy, Japanese biz guyz arrogantly referred to themselves as “economic tigers.” I was assigned by my teaching company to Honda Center in downtown Tokyo, the posh Aoyama district of Minato Ku, there to conduct a business English class. With English as the international language, the idea was to disseminate English-speaking Honda tigers throughout the known world.

As I waited for a company representative to show up and lead me to my class, I sat on an elevated level looking down into the reception room of Honda central, a steel-and-glass building shaped like an upright submarine rising out of zillion-dollar-a-foot property. The reception area therein resembled a posh country club split on two different levels, and I soon noticed I was overlooking a table below with two American businessmen. One older than the other, they were also waiting. A Honda representative also sat at the table, all three apparently awaiting a decision from the upper floors. They were, it seemed, angling for a Honda franchise.

As I waited for a company representative to show up and lead me to my class, I sat on an elevated level looking down into the reception room of Honda central, a steel-and-glass building shaped like an upright submarine rising out of zillion-dollar-a-foot property. The reception area therein resembled a posh country club split on two different levels, and I soon noticed I was overlooking a table below with two American businessmen. One older than the other, they were also waiting. A Honda representative also sat at the table, all three apparently awaiting a decision from the upper floors. They were, it seemed, angling for a Honda franchise.

The older American biz guy had papers spread out on their table while the younger one was on his feet. He kept pacing small circles around the table, hovering over the Japanese Honda representative they called Steve. It was also apparent that things were not going well for my countrymen.

Even though the Honda representative had an American name, “Steve,” he didn’t seem to understand English very well. So the blabbering young American kept having to repeat himself. Steve would rotate his head between the seated man troubling over the papers and the younger one squawking like a seagull overhead.

If the biz saps had been a little more familiar with Japanese strategies… Well, if that were so, they wouldn’t have been there in the first place. But those two shouldn’t have been there at all, they were so tall. Japanese school girls might get all goofy about tall American actors, but the business honchos think them a bit freakish. And they certainly don’t like to look up to anyone. They like others to be bowing— like Obama.

Furthermore, the arrangement of younger and older— senior and junior— would be familiar to the Japanese as a kohai/sempai relationship— older and younger brother. With the Japanese, however, the young kohai does not speak without the older sempai acceding, and even then he would speak only to verify what the older one had said. That wasn’t the case with the voluble younger American kohai. He kept yakking while Steve was trying to communicate with the older sempai. The kohai kept hovering over the table, prattling in a loud voice guaranteed to grate the nerves of anyone, much less a Japanese person. They were indeed a couple of saps, which is probably why the Honda chiefs sent a rep who could hardly understand English.

(Honda hires from the cream of the university crop. Plenty of fluent English speakers in the bin. I’ve been at social gatherings with student workers who showed better grasp of English than many of my American students simply because Japanese instruction is one continual test for basic grammar, syntax, and vocabulary. Besides, many have studied abroad. In this case Honda decided to send “Steve” instead.)

But the beauty part was when, as the boy man kohai nattered on, he made the gravest of errors in speaking to someone who does not enjoy a firm grasp of the language. Kohai was evidently trying to smooth over their dicey situation by using an idiomatic expression: “Well, Steve, I guess you got to go with the flow.”

Steve was puzzled.

“Go with the flow. We have to go with the flow”— making wavy motions with his hands like a hula dancer— You know how water flows and you go with the flow?”

Steve was still puzzled. He turned from the sempai and the papers he was shuffling to look up at the tall talker. “You know, the river?”— Kohai by that time paddling down an imaginary river with his hands— “How the river flows? The river flows and you go with the flow.”

Steve was still puzzled, and he remained just as puzzled by the several further attempts to represent at full throttle a river flowing. He was still puzzling over those mysterious river flow words by the time my hostess arrived and guided me away from that scene to a classroom.

Together we took a walk down the boulevard to another building Honda owned. The Pola building, which is pronounced with an “r.” It’s so indicative of how Japanese like to control by how they insist on using English names with Ls in them. So you have to say Pora Biruding.

After meeting with the new class, I was happy to discover how that particular group of Honda folks already commanded a credible English speaking ability— far better than Steve grappling with the river flow. These students were so conversant, in fact, that after class, as we stood waiting for an elevator, one student made a crack which was genuinely funny. A rare occasion, someone actually saying something witty. Usually those group situations are rather nerve-wracking small talk and difficulty in understanding. Someone attempts a witty remark and everyone forces a smile or a chuckle. But this remark— wish I could remember it— was funny. Got me to laughing quite heartily.

I was still chortling, face all contorted from laughter, as the elevator door opened. Packed within the cramped occupants were the two American reps from the reception hall, plus their cohorts. None looked like happy campers. None seemed to be going with the flow.

Kohai and sempai were there, so they’d been flushed to an out building as well. Other MBAs filled up the elevator car. It was obvious by their glum expressions that they didn’t get what they had flown across the Pacific to seek. The river had not only stopped flowing, but dried up as well. And every last face glowered in concert at the American laughing. Not only was he laughing with Japanese people, but Honda workers as well. They were still scowling bitterly as the elevator door closed upon them.

☞ Riding the subway home, a twinge of embarrassment, if not momentary guilt came over me. So sorry for my poor compatriots who’d lost the golden opportunity of selling more plastic Hondas. Their resentment was obvious at what must have looked like some collaborator yukking it up with the enemy. I didn’t even blame them. I thought for a moment I understood their disappointment, realizing how we all lose from a shrinking economy.

But then… Then it occurred to me that it was Homer Sap himself who cheered on the original thrust of the Great Global Gobble. And those recent counterparts, those two stooges were deluded into thinking they were going to get any more than what their “markets” want them to have. In this case, damn little.

It was Homer Sap, not me, who made a mess out of the largest industry in what was once the king of industrial nations. I didn’t insist on making and then hanging onto big goofy chrome monsters for cars; I myself was driving an MG. I didn’t bend over to accommodate destructive union greed. I didn’t try to make a sow’s ear out of a golden goose. I didn’t ignore the explosive sales of the first Datsuns and Toyotas in the 60s instead of tacking fins and gooping more chrome over a gigantic gas-guzzling iron sled with a runway for a hood, and then sell it as the “latest” model.

It was Homer Sap, not me, who made a mess out of the largest industry in what was once the king of industrial nations. I didn’t insist on making and then hanging onto big goofy chrome monsters for cars; I myself was driving an MG. I didn’t bend over to accommodate destructive union greed. I didn’t try to make a sow’s ear out of a golden goose. I didn’t ignore the explosive sales of the first Datsuns and Toyotas in the 60s instead of tacking fins and gooping more chrome over a gigantic gas-guzzling iron sled with a runway for a hood, and then sell it as the “latest” model.

If it were up to me, I would have stuck to the advanced car models like Kaiser and Studebaker. I would definitely have let the Tucker live. And I wouldn’t kotow to gangster-ridden unions. Maybe that would have kept enterprise more at home. So all of the saps who participated in the decline of that particular industry on the top floor of corporate America throughout the most inventive period in civilized history now have to bargain on a foreign-made car for their supper.

If it were up to me, I would have stuck to the advanced car models like Kaiser and Studebaker. I would definitely have let the Tucker live. And I wouldn’t kotow to gangster-ridden unions. Maybe that would have kept enterprise more at home. So all of the saps who participated in the decline of that particular industry on the top floor of corporate America throughout the most inventive period in civilized history now have to bargain on a foreign-made car for their supper.

Now that markets are almost entirely devoted to consumerism, staple supply off in a corner, remaining business has little to do with manufacturing, and everything to do with distributing marginally necessary products made elsewhere, usually Asia. All collateral systems— distributing, informational, etc— primary to dispersing bullshit.

Thus my two countrymen who represented one of the largest business sectors in the world went hat-in-hand, beseeching their old wartime enemies for a franchise or a purchase. As GM goes so goes the nation, was the motto. But down seems to be the direction GM is going— like a river. Homer Sap knows how to bend, but he doesn’t know how to bow. That’s essential in Japan, a low bow. Go with the flow.

II

☞ That personal Honda event occurred in the late 80s, but things have not changed for the better since. In fact, what recalled that experience here in the Trying Times bunker was the recent presidential election. Despite grave personal doubt in the beginning of his campaign, Donald Trump has at least allayed some of those doubts. As is said in business, nothing succeeds like success. His performance even promises the possibility of a leader who helps the Great Global Gobble to something closer to that mythical level playing field. Perhaps there may be a truly mutual exchange of interests, so often promised, yet never working out. Agreements always seem to work out the way Hamlet said, “more honored in the breach than the observance.” But President Trump at least signals the problem those breaches present.

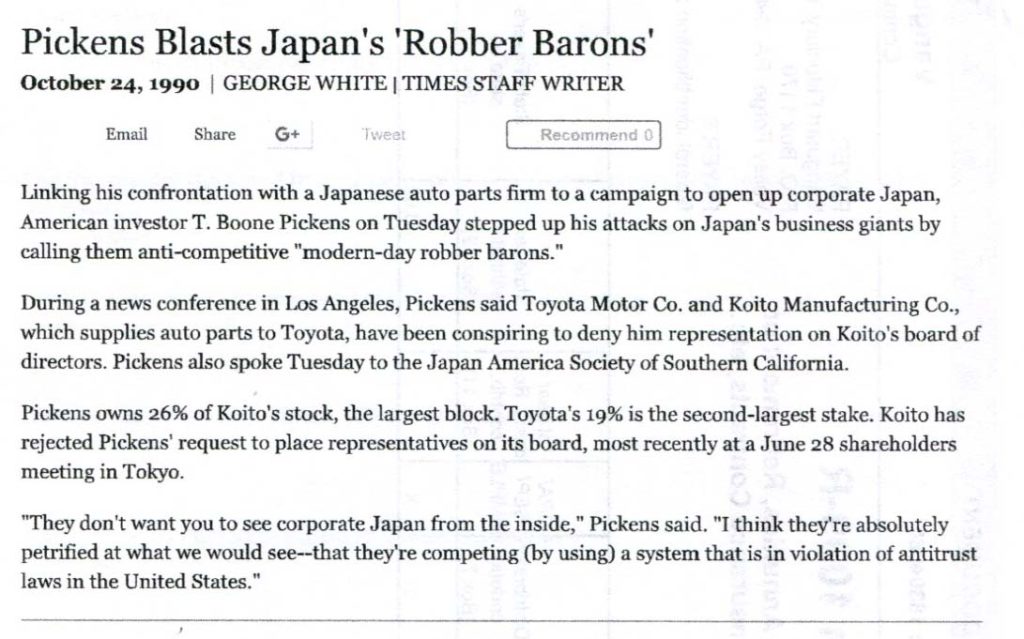

☞ It has always provoked a chuckle, the term “level playing field.” First of all, it’s not play. And it sure wasn’t to be seen at the Koito board room in Tokyo at the same time I was in that Honda biruding. Sure didn’t work out for T. Boone Pickens. (Always loved the name, it’s so Dickens)

Not long after my experience at Honda, the financier acquired a major holding in the Koito Group, an established auto electric monopoly. The good ol’ boys of the board, however, denied Pickens entry into the stockholder meetings. The American corporate raider obviously made the monopoly… er, excuse me, group owners nervous. So there was T Boone Pickens actually banging on the boardroom door while his Nipponese stockholder fellows were on the other side of it, probably

Not long after my experience at Honda, the financier acquired a major holding in the Koito Group, an established auto electric monopoly. The good ol’ boys of the board, however, denied Pickens entry into the stockholder meetings. The American corporate raider obviously made the monopoly… er, excuse me, group owners nervous. So there was T Boone Pickens actually banging on the boardroom door while his Nipponese stockholder fellows were on the other side of it, probably  stacking up furniture in a cold sweat.

stacking up furniture in a cold sweat.

To let the American in, you see, would have been difficult, muzukashi. Never mind when Japanese corporate interests are constructing real estate monopolies in Honolulu. That’s just part of free enterprise. You know, obliging the Great Global Gobble. But a foreigner, a gaijin with major holdings in Koito… That sort of thing on the sacred soil of our ancestors… Well, muzukashi desu ne? Difficult, isn’t it.

Anyone for a level playing field?

☞ But back to the Honda experience. While riding home afterward, a more uncomfortable thought popped into my head. Wasn’t I part of the trend? A qualified American English teacher teaching English to Honda workers and middle level managers. I myself had to “go global” and teach my own language where it was most desirable and profitable. So I suppose we all had to go with– you know– the flow.

☞ It’s been pretty much recognized by now that American goods are no better than the Japanese. The best things Americans seem to produce is the blues. Considering the quality of American automobiles of the sixties— when the Japanese began their bid to compete in that market— small wonder.

And this does not take into consideration that sea of other services implicit in Japanese society. When a Japanese service man agrees upon an appointed time at a quoted price, it has been my  experience that the agreement is as reliable as the performance of a Toyota. Whether it is tangible as quality goods, or intangible as service, the attitude seems equal, whereas agreements between American producers and consumers might be best expressed by one of the songs I played on my walkman while riding home from Honda.

experience that the agreement is as reliable as the performance of a Toyota. Whether it is tangible as quality goods, or intangible as service, the attitude seems equal, whereas agreements between American producers and consumers might be best expressed by one of the songs I played on my walkman while riding home from Honda.

It was a satirical song by Frank Zappa titled “Fresh Flakes,” which poked fun at the very thing I was musing over: failing American industry and the flakes who service it. A couple of telling lines from the song go like this:

All what we got here is American-made,

A little bit cheesy but nicely displayed.

As usual, the Big Zapper got it right. A little bit cheesy but nicely displayed indicates a bottom line based on the 3 Ps: packaging, promo, and pizazz. Nothing to do with substance. Not only nicely displayed are the products of marginal value, but enthusiastically glossed and vacuum-packed and hysterically promoted. Everything but the actual quality performance of the product. Nothing to do with quality control, an idea Japanese industry bought into with the ironic aid of an American: W. Edwards Deming. The economist marketeer went to Japan after he was unable to sell his idea of quality control to American companies. In Japan, business people practically bow their heads at the name of Deming-san.

Instead, we at the home of modern industrialism deal with the cheesy product wrapped in six layers of petroleum gloss— ghoul paper that can’t be torn, refuses to die or even be wadded up. We are forced to buy the piece of crap manufactured in China which doesn’t work when brought home. And the clerk gives you more crap when you return it. The waiter with the tag on his shirt (Call me Ron) drools over your soup as he asks: “Is everything wonderful?” When the steak is overdone, and it’s second grade meat to begin with because the choice stuff went to Japan. All in all, providing a superior product these days is rather dubious. Both the goods, as well as the services behind it, turn out to be too often little more than a heap of flimflammery and foofoofery.

Moreover, the curious part of all this is that the American worker usually ranks statistically among the highest as the most productive on the planet; the Japanese laborer one of the least. That breakdown of energy and efficiency is puzzling, but one thing may be deduced from such a fact: energy alone does not guarantee quality of product any more than a lot of lesser productive workers do not guarantee failure. And so much promotion does not necessarily help either. When more is spent on promises than the product or actual services, the result tends to be more than just “a little bit cheesy.”

So, I’m wondering, Is that what they mean by going with the flow?

JoCo

Comments are closed.