SPECIMEN: Remnant of a literate society:What life and Life Magazine were like.

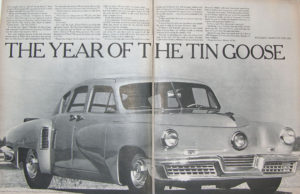

☞ In order to appreciate what Life was like when literacy was in flower, check out this full-page advertisement from the April 1967 edition. Observe, if you will, page layout: An ad of this size in a top-drawer popular magazine had to be the equivalent of a minute spot on a major TV channel today.

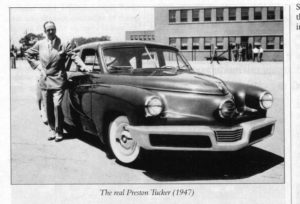

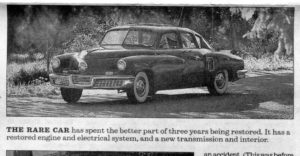

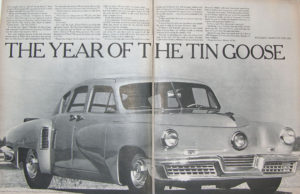

☞ Observe the picture: six columns of copy over the image of an especially rare automobile, The Tucker, which in itself symbolizes a moment of record in the history of auto American commerce. It exemplifies not only extraordinary design, but also tells the story of how wooden head-in-bum commercial and political interests stifle ingenuity. Experimentally built in 1947 with such advanced features as a padded dash, a pop-out windshield, and air-cooled rear engine, fluid drive, and yet was never produced for public consumption. The Tucker could have been the people’s car like the Volkswagen— minus the Nazis. But this marvel of innovation was eliminated before it was market-tested. Yet that isn’t the reason for using it in this 1967 Life Magazine advertisement.

☞ The Tin Goose was emblematic of a time when American engineering and design had peaked. Its status as a zenith of accomplishment was the reason for using its image as a theme for an advertisement pitch. The ad attempts to seduce the 1967 buyer /reader into purchasing not a Tucker automobile— for that would be impossible— but pitching instead a whiskey: Seagrams Crown Royal.

☞ The Tin Goose was emblematic of a time when American engineering and design had peaked. Its status as a zenith of accomplishment was the reason for using its image as a theme for an advertisement pitch. The ad attempts to seduce the 1967 buyer /reader into purchasing not a Tucker automobile— for that would be impossible— but pitching instead a whiskey: Seagrams Crown Royal.

☞ So why, we might then ask, is a photo of a car which was never sold used to sell some rotgut joy juice? How could we know to drink that particular whiskey when there’s not a picture of the bottle in sight, nor even a label? But that’s the point, silly! You must read the text. And it will take trudging through five columns of fine print for a clue into why a prototype Tucker is reason to drink Seagram’s Crown Royal whiskey. When you figure it out: Cheers!

☞ One thing’s sure: the writers of that torturous ad copy obviously took it for granted that readers would be willing to follow such a twisty path of logical analogy between marked events in 1947— year of the Tucker– and the birth year of their own product, which is not even mentioned until after reading nineteen lines of unexciting prose. Even though the pitch itself is as mediocre as the hooch it’s selling, snoring along as boringly as a dull TV commercial, there are worth noting certain historical artifacts resident in the actual writing. Mainly, archaic punctuation: dashes, semi-colons, underline, ellipses… Tell-tale signs of the literacy expected in any prose of the day, including goofy advertising.

[Tucker ad script I]

Some people called it “the car of the future.” Some people called it a fraud. But the men who built it called it simply and affectionately The Tin Goose. Maybe you remember the sensation it caused. Traffic jams in Chicago. Uneasiness in Detroit. Frenzy in New York where, in one September week, it outdrew every show on Broadway. And in empty showrooms all over the country signs began to appear. “Coming Soon .. .The New Tucker!” It was the year “Happy” Chandler, the czar of baseball, suspended Leo Durocher for the season. Gil Dodds held the indoor mile record at 4:06.4. They were building Kaisers in the big Liberator bomber plant at Willow Run. And skirts were so long that the only knees in sight belonged to Sally Rand. You danced to the music of Wayne King. And you listened to radio because television hadn’t yet become TV. Nobody had ever heard of transistors or mini-skirts or frozen pizza. That’s the way things were in 1947, the year that Seagram’s 7 Crown first became the world’s best-selling whiskey.

☞ The advertiser’s hubris is obvious enough: comparing a rather marvelous creation with mediocre whiskey. But that hubris was bought by contribution of another marvelous invention from another world: Johannes Gutenberg’s movable type printing press. Since Herr Gutenberg’s time, anyone with something to sell— church men and pitch men alike— relied on words to press a desire from religious belief to buying stuff. Collaterally, they also assumed a requisite logic inherent in the linear thinking print enforces. Mr. Baloney Man could never fly that 1967 ad today with words only that require the simplest logic. Mr Ad Man needs pictures like a junky needs his dope. Images. Preferably bikinis within sight of the product.

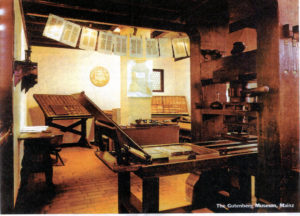

☞ Gutenberg was thwarted in his ambitions, like Preston Tucker, and he died poor. Creator of a whole galaxy of communication (The Gutenberg Galaxy, as McCluhan called it), he just plunked along in his last days on a stipend from the city of Mainz ; they at least realized what a gift he had given to humanity. So Johannes Gutenberg made another in the host of Manichaean tales, others who were shorted on glory as well as gelt for their achievement in the commercial world. We say Manichaean because the world does seem to fall in line with the ancient heretical view that the devil is running it. Bad men rewarded and good men’s deeds interred with their dust furthers a personal conviction that the devil is actually ignorance.

☞ Besides Tucker and Gutenberg, there was George Durant, who was actually able to succeed. But his success was far from assured at first. He found it impossible to get a rise out of any wooden-headed investor to back his idea; conventional business thinking couldn’t wrap its wooden head around combining smaller motor works, like Oldsmobile, to create a larger combined manufacturing concern— one by the name of General Motors.

☞ Besides Tucker and Gutenberg, there was George Durant, who was actually able to succeed. But his success was far from assured at first. He found it impossible to get a rise out of any wooden-headed investor to back his idea; conventional business thinking couldn’t wrap its wooden head around combining smaller motor works, like Oldsmobile, to create a larger combined manufacturing concern— one by the name of General Motors.

☞ After saving the Ford Motor Company’s ass with the ultra-modern Mustang classic, CEO Lee Ioccoca was the obvious man for the job. But he was not kept to be CEO of Ford Motor Company because the younger Ford did not want “the wop” running his pappy’s company. Among Ford II’s later wooden-headed choices was the Edsel flop, while the wop went on instead to save Chrysler.

☞ After saving the Ford Motor Company’s ass with the ultra-modern Mustang classic, CEO Lee Ioccoca was the obvious man for the job. But he was not kept to be CEO of Ford Motor Company because the younger Ford did not want “the wop” running his pappy’s company. Among Ford II’s later wooden-headed choices was the Edsel flop, while the wop went on instead to save Chrysler.

☞ Steve Jobs lost his job at Apple to a former Pepsi Cola CEO, the innovator being aced out by a tinhorn more versed in controlling stockholder boards than in designing circuit boards. The way Jobs lost his clout (besides being tyrannical) was the same manner in which Gutenberg lost his press. Jobs

☞ Steve Jobs lost his job at Apple to a former Pepsi Cola CEO, the innovator being aced out by a tinhorn more versed in controlling stockholder boards than in designing circuit boards. The way Jobs lost his clout (besides being tyrannical) was the same manner in which Gutenberg lost his press. Jobs  too busy designing equipment; Gutenberg too busy hustling investment and working on furthering his movable-type press with an illustrated lithographic process. In the fifteenth century ol’ Johan foresaw the modern printed page. Meanwhile, in-laws plotted, and he was forced into bankruptcy. So the only two things Gutenberg was able to create with his press was the Bible and a calendar based on the dire theme of Islam

too busy designing equipment; Gutenberg too busy hustling investment and working on furthering his movable-type press with an illustrated lithographic process. In the fifteenth century ol’ Johan foresaw the modern printed page. Meanwhile, in-laws plotted, and he was forced into bankruptcy. So the only two things Gutenberg was able to create with his press was the Bible and a calendar based on the dire theme of Islam  conquering the Eastern Roman Empire, anno. 1454.

conquering the Eastern Roman Empire, anno. 1454.

☞ Creations like those of Steve Jobs are presently vying to replace Herr Gutenberg’s. That remains to be seen— if the dynamos keep turning. Presently, the effects of electronic communication are putting their seal on everything, including the human brain— much as the printing press had. What the effects of Apple doodle boxes and the like will be in the long run is unpredictable. In the short run, however, they are affecting public attention, which is easily shown by how archaic the print form of the Seagram’s ad is. And that from 1967, a mere 45 years ago.

[Tucker ad script, II]

And today? Leo’s with the Cubs. Ebbets Field is overlaid with apartment houses. The Tin Goose (which never did get off the ground) and the Kaiser are both collector’s items. Instead of Wayne King you have The Lovin’ Spoonful. And Tom O’Hara owns the indoor mile record at 3:56.4! Staggering changes. In all aspects of our life. Especially our tastes. All in a matter of twenty years. Yet the whiskey that became number one in 1′ has been number one every year since. Today it is still the most asked-for whiskey in the world And by as wide a margin as ever. Think about that for a second. You’ve seen fads. You’ve seen fashions change, records fall. You know as well as anyone that a product which has stayed up there for two decades hasn’t stayed up there by accident. An avalanche of new whiskies from across the border and across the seas have tried to crowd it off the shelves. A host of rivals sell for less. But today Seagram’s 7 Crown is still number one. It’s first in the big cities and in the small towns; first in bars and in homes; first with younger drinkers and older drinkers; first in California and in Maine. And it has stayed in first place for a good reason, that elusive thing called quality… easy to say but terrifically hard to achieve.

☞ Only by the method of following the bouncing ball along the sequence of print— word by word by word— could the Mad Ave messenger assume that a reader would connect “The Tin Goose” (Tucker nickname) with the Dodgers, a famous stripper, a mediocre radio dance band– and then, finally, the great leap to Seagram’s whiskey. We may derive from this document a full measure of words: how they can hold the loftiest of thought or the lightest fluff. Or how they may pitch a booze that probably wouldn’t have made it on its own by word-of-mouth.

[Tucker ad script III]

Quality means that there are no bargains when you buy your grain. It means that you pick your ingredients not because the price is right but to make the flavor right. It means a drill sergeant’s attention to each detail, from scouring floors, to building barrels, to testing, testing and re-testing the whiskey itself. You end up spending extra time and money every step of the way. And the result is rather dramatic. Light-bodied whiskey. Whiskey that tastes better. And above all, whiskey with taste that never varies from bottle to bottle, from year to year, from coast to coast. Taste that never varies. That is the measure of quality in a whiskey. And in the end, no distiller can match the consistent quality of taste in Seagram’s 7 Crown simply because no distiller has Seagram’s facilities, resources and experience behind him. So far, so good. But what about tomorrow? Unsettling as it is, change is the rule of life. So hold on to your hat. The next twenty years will make the ones we’ve just been through seem tame. About the only thing you can be sure of is that in 1987 Seagram’s 7 Crown will still be first. Because it’s better whiskey. Always has been. Always will be.

SEAGRAM’S 7 CROWN/THE SURE ONE.

☞ This was just one cinder out of a volcano of ads spewing forth from Madison Avenue, New York, where the universe is centered. The abbreviated moniker for that enterprising location was Mad Ave, and the title seemed most appropriate. It had to be some form of madness where writers of this immortal copy were paid handsomely for phrases such as “Quality means that there are no bargains when you buy your grain.” Doesn’t that just put the tit in titillation?

☞ As a further bit of irony, this madness resides on a street named after one of the clearest writers, as well as thinkers, in American history. James Madison was the federal assembly member who wrote the copious notes from which not only the Federalist Papers were drawn, but also formed a guide to keep the framers on track in the writing process of the US Constitution. Therein lies the kicker: Madison, a writer of celebrated clarity, lent his name to a place where copy writers get rich on horse shit. And it’s not far from Washington, where some politicians and lot of legal eagles hanker to deconstruct the whole constitution, and Madison’s work in the bargain.

☞ And check it out— the actual product, Seagram’s Seven, is only mentioned thrice in all that pile of palaver, with nary a photo, nor even a simple drawing of a scantily dressed model, or a party full of drunks holding glasses. Simply the product name in bold caps. Total reliance on funky logic— and the word.

☞ Sitting in the audience of this post modern millennium, sippin’ a Jack Daniels, such an anachronistic advertisement plucked from the Trying Times archives drew wonder. What conclusions could be drawn? These are a couple.

☞ Sitting in the audience of this post modern millennium, sippin’ a Jack Daniels, such an anachronistic advertisement plucked from the Trying Times archives drew wonder. What conclusions could be drawn? These are a couple.

☞ This dry leaf of a page on a withering tree serves as a conclusion to mass print technology that exploded beginning with the first newsprint advertisement in 1704. As Neil Postman observed in Amusing Ourselves To Death: “If we may take advertising as the voice of commerce, then its history tells very clearly that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries those with products to sell… assumed that potential buyers were literate, rational, analytical.” (P.58)

☞ Imagine, literacy! And no bikinis! Do not misunderstand, serial oglers have no problem with them; bikinis are usually the best part of some ad offering a junk product. It’s only that bikinis serve to distract, as all else in this distracted society. “Indeed the history of advertising in America may be considered, all by itself,” Postman went on, “as a metaphor of the descent of the typographic mind, beginning as it does with reason, and ending, as it does, with entertainment.”

☞ One other thing is left out, but no surprise. Leaving things out is indeed the task of any good propagandist, who always skips the harsh stuff. But the reader might whiff a sniff of suspicious absence in that whole tedious background narration on Seagrams, bottom of the third column: “An avalanche of new whiskies from across the border and across the seas have tried to crowd it off the shelves.” Now what other kind of “avalanche” could have been in effect? What kind of force? Since Joseph Kennedy, Johnny’s daddy, bootlegged the hooch from across the Canadian border during Prohibition, we might ask: What other forces besides market competitors tried to keep Seagram’s off the shelves— feds or Mafia? Or maybe it was the Russians.

JoCo